In 1962 she married the actor Louis Zorich, and they were the artistic inspiration behind the Whole Theatre in Monclair, New Jersey (1973-1990), adapting plays for the company and directing dinner theatre there and at summer festivals elsewhere in the US. Laura Linney, left, and Olympia Dukakis in More Tales of the City, 1998. She was a founder member of the Charles Playhouse, Boston, where she worked from 1957 to 1960, and taught acting at New York University and at Yale. She gained a BA in physical therapy at Boston University, later returning to study performing arts for a master of fine arts degree.

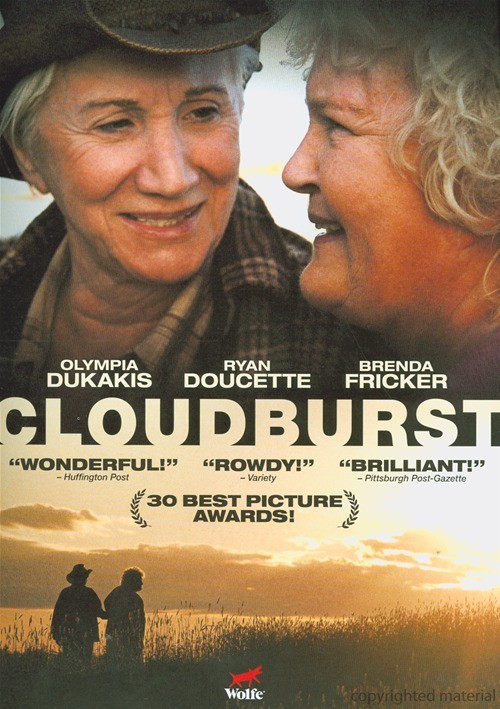

Cloudburst 2011 film movie#

This was underlined by Cloudburst (2011), a road movie in which Dukakis, as a self-styled “old butch dyke”, and her companion of 31 years (Brenda Fricker), take off from the US to Canada to get married.īorn in Lowell, Massachusetts, Olympia was the daughter of Constantine Dukakis and Alexandra (nee Christos), both Greek immigrants. She reappeared in the sequels, More Tales of the City (1998), Further Tales of the City (2001) and again under the title of Tales of the City (2019).īecause of this part and several other gay-friendly ones, Dukakis became a hero of the LGBTQ+ movement.

Cloudburst 2011 film tv#

But arguably her best role was in the TV mini-series Armistead Maupin’s Tales of the City (1993), as Anna Madrigal, the free-spirited, transgender, pot-smoking landlady in 1970s San Francisco. In Dad (1989), as a woman laid up with a heart attack watching her husband ( Jack Lemmon) enjoying a certain freedom, she is wickedly funny, putting a tincture of venom into almost every line.ĭukakis continued to be much in demand in the movies, with roles such as Jocasta in Woody Allen’s Mighty Aphrodite (1995), and the stern but lovable school principal in Mr Holland’s Opus (1995). Photograph: AA/AlamyĪmong the best were the tight-lipped personnel officer in Working Girl (1988) the archetypal comic “Jewish mother” of Kirstie Alley in Look Who’s Talking (1989) and its two sequels and the acid-tongued Clairee Belcher, trading a salvo of one-liners with Shirley MacLaine in Steel Mangolias (1989): “Well, you know what they say: if you don’t have anything nice to say about anybody, come sit by me.” Shirley MacLaine, left, with Olympia Dukakis in Steel Magnolias, 1989.

Winning the Oscar led inevitably to more recognition, though not necessarily bigger parts. “Feed one more bite of my food to your dogs, old man, and I’ll kick you to death,” she tells her father-in-law at the dinner table. In Norman Jewison’s Moonstruck, a modern fairytale of love, with each leading character destined to have his or her moment of glory, Dukakis is by turns warm, humorous and cynical, and poignantly wonders why men (especially her husband) are unfaithful. In one scene, she remains hostile until, alone in the hallway, she shrieks: “Get that woman out of my house.” In Made for Each Other (1971), a romantic comedy in which an Italian-American man ( Joseph Bologna) and a Jewish woman (Renee Taylor) fall in love, Dukakis is the former’s mama opposed to her son’s relationship. The first of her many mother parts came in Peter Yates’s John and Mary (1969) seen briefly in flashback as Dustin Hoffman’s mother. Photograph: APL Archive/Alamyĭukakis made her film debut as a patient in a mental hospital in Robert Rossen’s Lilith (1964).

Olympia Dukakis, left, with Cher in Moonstruck.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)